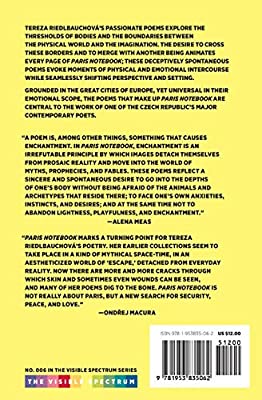

“These poems are pleasingly, vigorously on the move. The book draws on the European traditions of absurdism and surrealism…And there are deep feelings and struggles contained here, though often expressed with a lightness of touch.” — Charlotte Wetton, Modern Poetry in Translation

About the book

By Tereza Riedlbauchová

Translated from the Czech by Stephan Delbos

Paris Notebook is the lyrical record of a poet’s quest for human unity and wholeness. Tereza Riedlbauchová’s intensely passionate poems explore the thresholds and ruptures of bodies and the boundaries between the physical world and the imagination. The desire to pass beyond these borders and emerge elsewhere, or to merge with an- other living being, animates deceptively spontaneous poems evok- ing moments of physical and emotional intercourse while seamlessly shifting between different perspectives and settings.

Riedlbauchová wrote Paris Notebook between 2008 and 2012 when she was living mostly in Paris, but these poems are not confined to the French capital. Barcelona, Île de Ré, Normandy, Plovdiv, Rome, Prague, and rural areas of the Czech Republic are all visited. This pan-European scope adds a deep and varied sense of place to the collection while also articulating Riedlbauchová’s transnational poetics.

Reviews

“The poems of Tereza Riedlbauchová flare and ghost with images and atmospheres of traces left, boundaries blurred, and the movement toward connection. Paris Notebook (Visible Spectrum), a new volume of the contemporary Czech poet’s work, translated by Plymouth-based poet and translator Stephan Delbos, showcases a dreamy lyricism that nods now and then to the deep dark macabre: ‘I stood on the threshold / below me lay a dead woman / in the shape of the day before.’ Her poems are sensual, too, and open to the body and its beauties and horrors. Part of her lover’s body ‘bridges all the rivers and / halts at the midpoint of all the seas.’ Delbos, who serves as poet laureate of Plymouth, offers a deft, sensitive translation, and gives thoughtful context to Riedlbauchová’s work in his afterword, noting her place in Czech, European, and transnational poetic traditions. There are whispers of exuberant despair — ‘from now on nothing matters to me’ — and haunting moments of truth — ‘autumn like a swallowing flower.’ — Nina MacLaughlin, The Boston Globe

“These poems are pleasingly, vigorously on the move. The book also draws on the European traditions of absurdism and surrealism…And there are deep feelings and struggles contained here, though often expressed with a lightness of touch. Here are existential concerns about how we can relate to other people and places, how we can move through the world. Not only the geographic locations of the book – Normandy, Rome etc – but how we inhabit and conceive of spaces in relation to others. Desire thrums through the book; the erotic, but also the desire to experience and understand, and the fear that comes with that. Often the poems’ dream-like state takes us into a symbolic realm, a place suggestive of deeper knowing, playful and painful in turn. It is possible to sit for a long time with one piece, examining its entirety from different perspectives, weighing the truth of it.” — Charlotte Wetton, Modern Poetry in Translation

“In addition to the virtuosity of the poet, this sense of wholeness discovered in the ruptured and incomplete owes a great deal to the skill of the translator, Stephan Delbos… One of the greatest challenges such work entails is resisting the temptation to “overdesign” our sentences. Different languages make logical connections differently. A relationship between two ideas that can be expressed in a straightforward and unmarked way in one language may often sound convoluted in another, which means that translators of poetry constantly run the risk of producing overly elaborate sentences in a misguided attempt to imitate the grammar of the original. That risk is compounded when working with Czech, which, as Delbos notes in his afterword, offers freer word order than English, and a lesser translator might have clogged the text with unnecessary logical-connector prepositions in an attempt to make up for that lost syntactical freedom. Since the aesthetic value of Riedlbauchová’s poetry depends so heavily on her distinctively uncluttered “freestanding” lines, this would have been a tragic mistake, and the translator deserves to be commended for avoiding it. Furthermore, this translation is remarkably successful at reproducing the sound of the original, including subtle devices like consonance and assonance.” —Isaac Stackhouse Wheeler, Apofenie